Patience in life

If childhood had a list of universal lessons, patience would hold a privileged place—right next to learning to share toys and tie shoelaces. From an early age, we are told that «patience is a virtue,» as if it were something we could simply switch on and off at will. «Wait your turn,» «Don’t interrupt,» «Everything happens in its own time.» Phrases we hear over and over, yet rarely are we taught how to apply them when everything around us pushes us toward immediacy.

The problem is that we live in a society that does not reward waiting. We want quick answers, instant results, and immediate rewards. Children grow up with technology that provides entertainment in seconds, surrounded by adults rushing from one task to another with no time for pauses, absorbing the idea that what is good must be fast—and if it isn’t, then it isn’t worth it. So, how can we ask them to be patient when everything around them screams that they shouldn’t wait?

The real issue is not just impatience but the frustration that comes with it. When something doesn’t happen immediately, a sense of despair takes over, as if waiting were synonymous with failure. Children cry because their drawing isn’t perfect on the first try, teenagers abandon projects because they don’t see immediate results, adults give up too soon because they’ve learned that if something isn’t quick, it’s not worth pursuing.

But here’s the great truth: patience is not just the ability to wait but knowing what to do while waiting. It’s understanding that the greatest achievements don’t happen overnight, that continuous effort has value, and that what matters is not just the result but the process. Patience teaches us to manage frustration, develop perseverance, understand that not everything is under our control—and that this is okay.

Ironically, adults are not masters of patience either. We live in a rush, jumping from one activity to another, demanding constant productivity, and measuring our success by how quickly we achieve our goals. We get frustrated in traffic, lose our temper in grocery store lines, and grow impatient when a message isn’t answered immediately. We want everything now, at this very moment, and without realizing it, we pass this same urgency on to our children.

Perhaps it’s time to rethink our relationship with time and waiting. Instead of seeing patience as a burden, we could start recognizing it as an opportunity to reflect, to enjoy the present, and to build calmly toward our goals. Accepting that not everything has to happen immediately allows us to appreciate small progress, moments of pause, and the processes that, though slow, lead to stronger results.

Amid this constant rush, we forget that life is not just about getting there fast but about enjoying the journey. We miss valuable moments in our obsession with meeting deadlines, checking tasks off an endless list, and feeling productive at all costs. Maybe patience is not just a virtue but a reminder that not everything has to be immediate. That waiting is not wasting time but giving value to each step. That taking a deep breath in traffic, enjoying a conversation without checking the clock, or letting children do things at their own pace is also living. Because, in the end, it’s not about how fast we arrive, but how we choose to travel the path.

La paciencia en la vida

Si la infancia tuviera una lista de lecciones universales, la paciencia ocuparía un lugar privilegiado, justo al lado de aprender a compartir los juguetes y atarse los cordones de los zapatos. Desde pequeños, nos dicen que «la paciencia es virtud de sabios», como si fuera algo que simplemente podemos encender y apagar a voluntad. «Espera tu turno», «No interrumpas», «Todo llega a su debido tiempo». Frases que escuchamos una y otra vez, pero que pocas veces nos explican cómo aplicar cuando todo en nuestro alrededor nos empuja a la inmediatez.

El problema es que vivimos en una sociedad que no premia la espera. Queremos respuestas rápidas, resultados inmediatos y recompensas al instante. Los niños crecen con tecnología que les da entretenimiento en segundos, con adultos que corren de un lado a otro sin tiempo para pausas, con la idea de que lo bueno es rápido o, sino es así, no vale la pena. Entonces, ¿cómo les pedimos paciencia cuando todo a su alrededor les grita que no esperen?

El verdadero problema no es solo la impaciencia, sino la frustración que viene con ella. Cuando algo no sucede de inmediato, el sentimiento de desespero aparece, como si la espera fuera sinónimo de fracaso. Niños que lloran porque su dibujo no quedó perfecto al primer intento, adolescentes que abandonan un proyecto porque no ven resultados inmediatos, adultos que se rinden antes de tiempo porque han aprendido que si algo no es rápido, no vale la pena.

Pero aquí está la gran verdad: la paciencia no es solo la capacidad de esperar, sino de saber qué hacer mientras esperamos. Es entender que los mejores logros no llegan de inmediato, que el esfuerzo continuado tiene valor, y que lo importante no es solo el resultado, sino el proceso. La paciencia enseña a manejar la frustración, a desarrollar perseverancia, a entender que no todo está bajo nuestro control y que eso está bien.

Curiosamente, los adultos tampoco somos maestros de la paciencia. Vivimos acelerados, corriendo de una actividad a otra, exigiéndonos productividad constante y midiendo nuestro éxito en función de lo rápido que logramos nuestras metas. Nos frustramos en el tráfico, perdemos la calma en las filas del supermercado y nos impacientamos cuando un mensaje no es respondido de inmediato. Queremos todo ya, ahora, en este instante, y sin darnos cuenta, transmitimos esa misma urgencia a nuestros hijos.

Tal vez sea momento de repensar nuestra relación con el tiempo y la espera. En lugar de ver la paciencia como un peso o una carga, podríamos empezar a reconocerla como una oportunidad para reflexionar, para disfrutar del presente y para construir con calma lo que queremos lograr. Aceptar que no todo tiene que suceder de inmediato nos permite apreciar los pequeños avances, los momentos de pausa y los procesos que, aunque lentos, nos llevan a resultados más sólidos.

En medio de esta prisa constante, olvidamos que la vida no se trata solo de llegar rápido, sino de disfrutar el camino. Nos perdemos momentos valiosos por la obsesión de cumplir con plazos, de tachar tareas en una lista interminable, de sentirnos productivos a toda costa. Quizás la paciencia no sea solo una virtud, sino un recordatorio de que no todo tiene que ser inmediato. Que esperar no es perder el tiempo, sino darle valor a cada paso. Que respirar hondo en el tráfico, disfrutar de una conversación sin mirar el reloj, o dejar que los niños hagan las cosas a su propio ritmo también es vivir. Porque al final, no se trata de cuán rápido llegamos, sino de cómo elegimos recorrer el trayecto.

EP6 Dialoguemos la Infancia

EP 6 Adolescentes en modo filósofo.

¿Tu hijo ahora debate contigo como si estuviera en la ONU, te lanza preguntas existenciales a la hora de la cena y cambia de identidad más rápido que su foto de perfil?. Bienvenidos a la adolescencia según Piaget y Vygotsky: donde el pensamiento se vuelve abstracto, las ideas se disparan y las galletas… se convierten en símbolos de justicia social. En este episodio hablamos de cerebros en modo filósofo, dilemas morales, TikTok, ropa existencial y la épica lucha por decidir con quién se parte la última galleta. Spoiler: no es solo una galleta. Prepárate para reír, entender y tal vez identificarte más de lo que creías.

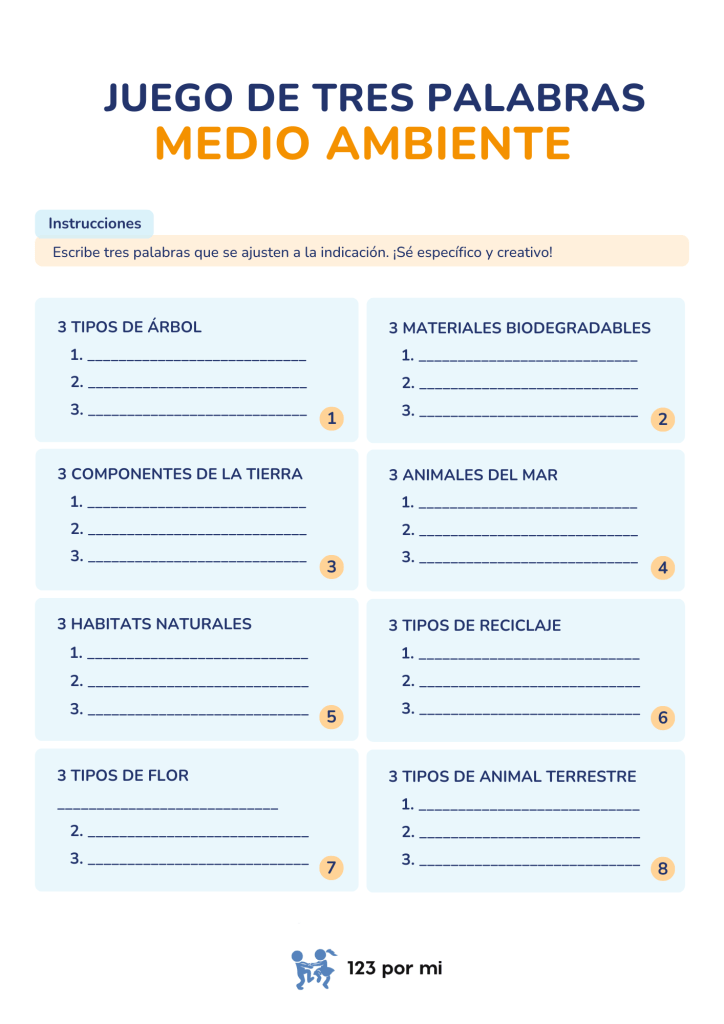

Juego de 3 palabras

Laberinto de adjetivos

Raising twins

If being a parent is already a challenge worthy of a survival reality show, raising twins is basically playing in expert mode with a split screen. From the moment you discover two (or more) beating hearts on the ultrasound, people start asking questions and making assumptions as if they were experts: «Are you going to dress them the same?», «Do they have the same personality?», «Who’s the leader and who follows?» As if sharing DNA meant sharing personalities, tastes, and even destiny.

We grow up with the romanticized idea that twins are two halves of a whole, soulmates from the cradle who think and feel the same. And while the bond between siblings can be wonderful, there’s something that often gets overlooked: each child is an individual. Even if they were born on the same day, even if they look exactly alike, even if they have a secret language that adults can’t decipher.

From day one, parents of twins face an extra challenge: fostering their individuality in a world that insists on seeing them as a two-for-one package. Sometimes, without realizing it, we reinforce this idea in small but significant ways: calling them «the twins» instead of by their names, buying them identical clothes, enrolling them in the same activities, or assuming that if one likes soccer, the other will love it too.

But here’s the truth: every child, even if they share genetics and a bedroom with their sibling, has their own voice, their own rhythm, their own preferences, and their own dreams. And recognizing this isn’t just important—it’s essential. Giving them space to develop their own interests, respecting their differences, and allowing them to make individual choices is a gift that will stay with them for life. Being a twin isn’t an identity in itself; it’s just one part of who they are.

For example, some twins may have completely opposite personalities: one might be outgoing while the other is more reserved, one might love sports while the other is passionate about music. And the funny thing is that, even though many people see them as a unit, they often feel the need to differentiate themselves. It’s common for twins, as they reach adolescence, to seek to define their identity more distinctly.

Parents play a fundamental role in this process. Creating moments of individuality within their routine is key. Allowing each child to have their own space, their own friendships, and their own interests—without the pressure of fitting into a predetermined mold—is essential. It’s also important to avoid constant comparisons between them. Phrases like «Your brother does it better» or «You should learn from him» can create unnecessary competition and affect their self-esteem. Comparisons can make them feel pressured to meet external standards instead of exploring and embracing their own strengths. After all, every child has their own learning pace, their own way of processing the world, and their own talents. Recognizing their individual achievements without contrasting them with their sibling’s allows them to grow with confidence and without the weight of imposed rivalry.

And yes, there will be days when it’s easier to treat them as a unit—because the logistics of raising two children the same age is chaos in itself—but the extra effort of seeing them as individuals is worth it. Because at the end of the day, the most valuable thing you can give a child (or two at the same time) is the certainty that they are seen, heard, and loved for who they truly are.

So if you’re a parent of twins and wondering if you’re doing the right thing, here’s a small compass: ask yourself if you’re raising them as a unit or as two unique individuals. And if you ever have doubts, remember this: it’s not about separating them, but about allowing them to be who they are. Because the best gift you can give them isn’t just a sibling to share life with, but the freedom to be themselves. At the end of the day, what matters isn’t that they are «the Pérez twins» or «the García brothers,» but that they are simply themselves—with their own name, their own essence, and their own path.

La crianza de gemelos o mellizos

Si ser padre ya es un reto digno de un reality show de supervivencia, criar gemelos o mellizos es básicamente jugar en modo experto con la pantalla dividida. Desde el momento en que descubres que hay dos (o más) corazones latiendo en el ultrasonido, la gente empieza a hacer preguntas y suposiciones como si fueran expertos en el tema: «¿Los vas a vestir igual?», «¿Tienen el mismo carácter?», «¿Quién es el líder y quién sigue?». Como si compartir ADN significara compartir la personalidad, los gustos y hasta el destino.

Crecemos con la idea romántica de que los gemelos son dos mitades de un todo, almas gemelas desde la cuna que piensan y sienten lo mismo. Y aunque la conexión entre hermanos puede ser maravillosa, hay algo que a menudo se pasa por alto: cada niño es un individuo. Incluso si nacieron el mismo día, incluso si se parecen la misma gota de agua, incluso si tienen un idioma secreto que los adultos no pueden descifrar.

Desde el primer día, los padres de gemelos y mellizos enfrentan un reto extra: fomentar su individualidad en un mundo que insiste en verlos como un paquete de dos por uno. A veces, sin darnos cuenta, reforzamos esta idea con detalles pequeños pero significativos: llamarlos «los gemelos» en lugar de por su nombre, comprarles la misma ropa, inscribirlos en las mismas actividades o asumir que, porque a uno le gusta el fútbol, al otro también le encantará.

Pero aquí está la realidad: cada niño, incluso si comparte genética y una habitación con su hermano, tiene su propia voz, su propio ritmo, sus propios gustos y sus propias esperanzas. Y reconocerlo no es solo importante, ES ESENCIAL. Darles espacio para desarrollar sus propios gustos, respetar sus diferencias y permitirles tomar decisiones individuales es un regalo que los acompañará toda la vida. Es recordar que ser gemelo no es una identidad en sí misma; es solo una parte de quienes son.

Por ejemplo, algunos gemelos pueden tener personalidades opuestas: uno extrovertido y el otro más reservado, uno amante de los deportes y el otro apasionado por la música. Y lo más curioso es que, aunque muchas personas los vean como una unidad, ellos mismos pueden sentir la necesidad de diferenciarse entre sí. Es común que los hermanos gemelos, al llegar a la adolescencia, busquen definir su identidad de manera más marcada.

Los padres juegan un papel fundamental en este proceso. Crear momentos de individualidad dentro de la rutina es clave. Permitir que cada uno tenga su propio espacio, sus propias amistades, sus propios intereses, sin la presión de encajar en un molde predeterminado. También es importante evitar la comparación constante entre ellos. Frases como «tu hermano lo hace mejor» o «deberías aprender de él» pueden generar sentimientos de competencia innecesaria y afectar la autoestima de ambos. Compararlos puede hacer que se sientan presionados a cumplir con estándares ajenos en lugar de explorar y aceptar sus propias fortalezas. Después de todo cada niño tiene su propio ritmo de aprendizaje, su propia manera de procesar el mundo y sus propios talentos. Valorar sus logros individuales sin ponerlos en contraste con los de su hermano les permite desarrollarse con confianza y sin el peso de una rivalidad impuesta.

Y sí, puede que haya días en los que sea más fácil tratar todo en conjunto—porque la logística de criar dos niños de la misma edad es un caos en sí mismo—pero el esfuerzo extra de verlos como individuos vale la pena. Porque al final del día, lo más valioso que puedes darle a un hijo (o a dos al mismo tiempo) es la certeza de que es visto, escuchado y amado por quien es.

Así que si eres padre de gemelos o mellizos y te preguntas si estás haciendo lo correcto, aquí tienes una pequeña brújula: pregúntate si los estás criando como una unidad o como dos personas únicas. Y si alguna vez dudas, recuerda esto: no se trata de separarlos, sino de permitirles ser quienes son. Porque el mejor regalo que puedes darles no es solo un hermano con quien compartir la vida, sino la libertad de ser ellos mismos. Al final del día, lo importante no es que sean «los gemelos Pérez» o «los hermanos García», sino simplemente ellos, con su propio nombre, su propia esencia y su propio camino.

Completa los datos del T-Rex

Frustration on children

If childhood had a list of inevitable experiences, school frustration would be in the top five, right alongside scraped knees and fights over who gets to play with the ball first. From an early age, we are taught that grades reflect our effort, intelligence, and, for some parents, even our worth as individuals. It doesn’t matter if you’ve learned something valuable in the process—if the result isn’t a perfect 10 (or an A+ for the more international crowd), the first thing you hear is: “Why didn’t you get a higher grade?”

The problem isn’t just academic pressure; it’s the imposition of perfection as the only valid goal. We grow up believing that making mistakes equals failure, that anything less than “excellent” is not good enough, and that if you just try hard enough, you should be able to get everything right, always. Spoiler alert: this isn’t true. And yet, here we are, watching kids and teenagers struggle because an 8 in math makes them feel like they’ll never be Einstein, or because a red mark on their essay feels like a judgment on their very existence.

Perfectionism isn’t just about wanting to improve; it’s the constant fear of disappointing others, of not being enough, of failing to meet the expectations of parents who, despite their good intentions, sometimes forget that their children aren’t robots programmed for automatic success. Phrases like “You have to be the best,” “You can always do better,” or “Why aren’t you like your cousin, who always gets straight A’s?” pierce a child’s self-esteem like darts, leaving a mark that’s hard to erase.

But here’s the great irony: real learning doesn’t happen in perfection; it happens in mistakes. The frustration of not getting something right the first time isn’t failure—it’s part of the process. And yet, many children grow up without permission to fail. Not because they don’t want to do well, but because they feel like their worth depends on it. As a result, the fear of failure turns into paralysis, anxiety replaces curiosity, and school stops being a place for learning and becomes a battlefield where the only goal is to win—or, in this case, to get the highest grades.

So, what can we do as adults to prevent school frustration from becoming a permanent shadow? First, change the conversation. Instead of asking, “Why didn’t you get a higher grade?” we can ask, “How did you feel about what you learned?” Instead of demanding perfection, we can value effort and progress. And most importantly, instead of making grades the center of school life, we can remind children that they are so much more than a number on a report card. It’s also essential to create an environment where learning itself is celebrated, where curiosity matters more than memorization, and where creativity and problem-solving skills are valued beyond a numerical grade.

Because at the end of the day, what we really want isn’t for kids to get straight A’s in every subject—it’s for them to grow up with the confidence that making mistakes is okay, that they can always improve without feeling like they’re not enough, and that their value doesn’t depend on a grade but on who they are as people. If we can help children associate learning with personal growth instead of fear of failure, we will be giving them an invaluable tool for life. And if you ever doubt whether you’re demanding too much, remember this: the goal isn’t to raise perfect kids, but happy, curious, and self-assured ones. Because true excellence isn’t in the final grade—it’s in the love for learning without fear of failure and in the ability to face challenges with resilience and confidence.