Up: flying when everything weighs

There are films that begin with a story. Up begins with an entire life. In less than five minutes, Pixar tells us a love story that is also a story about time, desire, small losses, and the final blow. Carl and Ellie’s story is so profound that it needs no dialogue: only silences, gestures, shared routines. And, of course, the house: that space that, in environmental psychology, can be understood as the physical extension of the self. In Up, that house becomes literal: it is the past that Carl refuses to let go of. His memory. His floating grief.

Carl represents old age from an emotionally dense perspective. He is not just an older man; he is someone clinging to nostalgia, to «what could have been.» Grief, as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross proposes, has five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Carl, at the beginning of the film, is caught between denial and anger. He’s turned his house into a time capsule, and any attempt at change (the construction of buildings, workers knocking on his door, the passing of the world) is a direct threat to his emotional stability.

But then Russell arrives.

From the perspective of child developmental psychology, Russell is a child who needs to belong. His insistence on earning a badge isn’t just a concrete goal: it’s his way of seeking validation, affection, and connection. We know he doesn’t have a father figure present, and that behind his insistence on helping the elderly lies a deep need for guidance, a look, and a hug.

Vygotsky argued that learning occurs in the zone of proximal development, that is, in that intermediate space between what a child can do alone and what they can do with help. Interestingly, Up reverses this concept: it’s the child who helps the adult overcome their limits. It’s Russell who pushes Carl toward transformation. Because Carl isn’t just old. He’s stuck.

The balloon ride—that powerful visual metaphor—is also an internal journey. It’s a metaphor for the need to let go of the weight, to literally release objects in order to keep moving forward. The house flies, yes. But it gets lower and lower. Every memory, every object, every chair prevents Carl from moving forward. Until he finally understands: he doesn’t need to take everything with him to preserve what’s important. Memory isn’t in things. It’s in the connection.

And that album, «My Adventure Book,» is the most powerful psychological twist in the entire film. Carl believed he had failed Ellie, that they hadn’t fulfilled their dream of going to Paradise Falls. But Ellie had already written her ending. The important thing wasn’t the destination. It was the shared life. The daily adventures. The little things. From an existentialist perspective, this is a stroke of lucidity: it’s not about what we dream of doing, but how we live in the meantime.

Up is also a study of intergenerational bonds. Carl and Russell need each other. One represents experience, structure, the past. The other, spontaneity, emotion, openness to the present. Together they find a middle ground. One lets go. The other feels seen.

And of course, Up also has its «cookie crisis.» But here, it’s a crisis shaped like a mailbox. When Carl hits a worker for touching the mailbox he shared with Ellie, we understand that this isn’t a simple reaction: it’s a desperate cry to not lose what little remains of their love story. It’s when the past hurts so much that it turns into violence.

But the film teaches us that true love isn’t lost when we move forward. On the contrary. Only when we move forward can that love be transformed into a legacy, a bond, a new story.

Thus, Up isn’t a movie about flying. It’s a movie about learning to let go of what we no longer need, so that what truly matters can… lift us up.

Up: volar cuando todo pesa

Hay películas que inician con una historia. Up inicia con una vida entera. En menos de cinco minutos, Pixar nos cuenta una historia de amor que es, también, una historia sobre el tiempo, el deseo, las pérdidas pequeñas y el golpe definitivo. La historia de Carl y Ellie es tan profunda que no necesita diálogos: solo silencios, gestos, rutinas compartidas. Y, claro, la casa: ese espacio que, en psicología ambiental, puede entenderse como la extensión física del yo. En Up, esa casa se vuelve literal: es el pasado que Carl se niega a soltar. Su memoria. Su duelo flotante.

Carl representa la vejez desde una perspectiva emocionalmente densa. No solo es un hombre mayor; es alguien aferrado a la nostalgia, al «lo que pudo haber sido». El duelo, como lo plantea Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, tiene cinco etapas: negación, ira, negociación, depresión y aceptación. Carl, al inicio de la película, está atrapado entre la negación y la ira. Ha convertido su casa en una cápsula del tiempo, y cualquier intento de cambio (la construcción de edificios, los trabajadores que tocan a su puerta, el paso del mundo) es una amenaza directa a su estabilidad emocional.

Pero entonces llega Russell.

Desde la psicología del desarrollo infantil, Russell es un niño que necesita pertenecer. Su insistencia en ganarse una insignia no es solo una meta concreta: es su forma de buscar validación, afecto, conexión. Sabemos que no tiene una figura paterna presente, y que tras su insistencia por ayudar a los ancianos hay una necesidad profunda de recibir guía, mirada, abrazo.

Vygotsky planteaba que el aprendizaje se da en la zona de desarrollo próximo, es decir, en ese espacio intermedio entre lo que el niño puede hacer solo y lo que puede hacer con ayuda. Curiosamente, Up invierte este concepto: es el niño quien ayuda al adulto a superar sus límites. Es Russell quien empuja a Carl hacia la transformación. Porque Carl no solo está viejo. Está estancado.

El viaje en globo —esa metáfora visual tan potente— es también un viaje interno. Es una metáfora de la necesidad de soltar el peso, de literalmente liberar objetos para seguir avanzando. La casa vuela, sí. Pero cada vez más baja. Cada recuerdo, cada objeto, cada silla, impide que Carl siga adelante. Hasta que finalmente lo entiende: no necesita llevarlo todo para conservar lo importante. La memoria no está en las cosas. Está en el vínculo.

Y ese álbum, el “My Adventure Book”, es el giro psicológico más potente de toda la película. Carl creía que le había fallado a Ellie, que no habían cumplido su sueño de ir a Cataratas del Paraíso. Pero Ellie ya había escrito su final. Lo importante no era el destino. Era la vida compartida. Las aventuras cotidianas. Las pequeñas cosas. Desde una mirada existencialista, esto es un golpe de lucidez: no se trata de lo que soñamos hacer, sino de cómo vivimos mientras tanto.

Up es, también, un estudio sobre los vínculos intergeneracionales. Carl y Russell se necesitan mutuamente. Uno representa la experiencia, la estructura, el pasado. El otro, la espontaneidad, la emoción, la apertura al presente. Juntos encuentran un punto medio. Uno suelta. El otro se siente visto.

Y claro, Up también tiene su “crisis de la galleta”. Pero aquí, es una crisis con forma de buzón. Cuando Carl golpea a un trabajador por tocar el buzón que compartía con Ellie, entendemos que no se trata de una simple reacción: es un grito desesperado por no perder lo poco que queda de su historia de amor. Es cuando el pasado duele tanto que se convierte en violencia.

Pero la película nos enseña que el amor verdadero no se pierde cuando se avanza. Al contrario. Solo cuando se avanza, ese amor puede transformarse en legado, en vínculo, en nueva historia.

Así, Up no es una película sobre volar. Es una película sobre aprender a dejar caer lo que ya no necesitamos, para que lo que realmente importa… nos eleve.

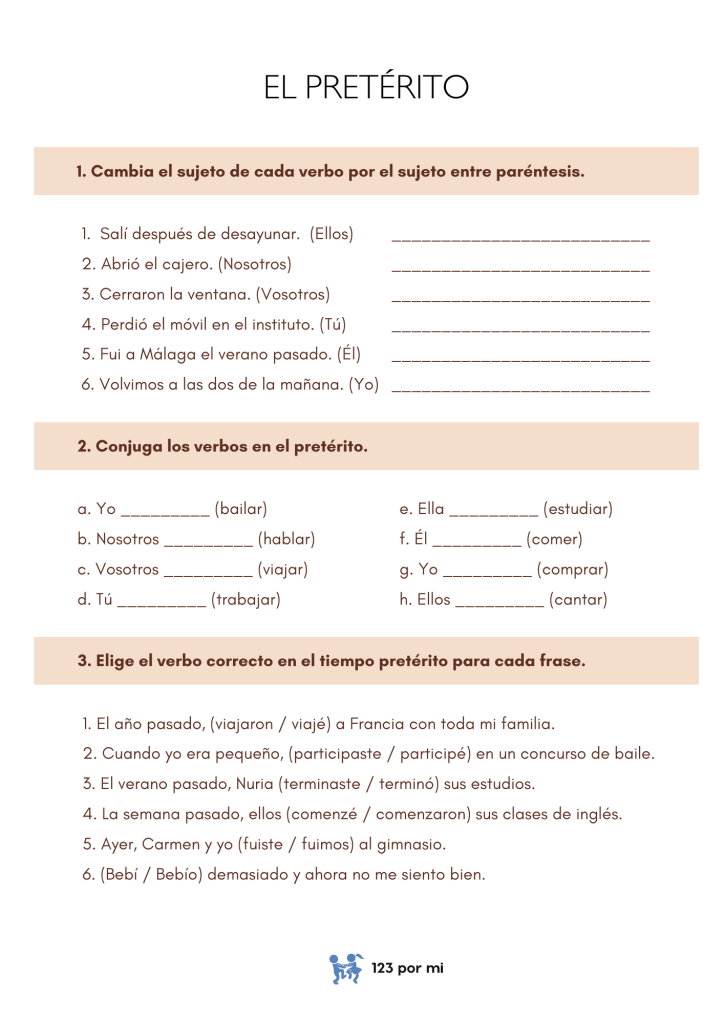

El imperfecto

El futuro

El pretérito

Nuevo episodio de Dialoguemos la infancia

Late adolescence

Late adolescence, that glorious stage that begins roughly between ages 17 and 21 (though it sometimes seems to extend into the 30s, depending on the case), is a time of major changes, life-altering decisions, existential questions, and, of course, an abundance of identity crises. It’s the phase when children begin to experience a sort of independence with a curfew—when they can technically move out, but still come home to do laundry and ask for groceries. They no longer contradict you just for sport; now they study degrees with names you didn’t even know existed, like “Computational neuroscience with a focus on artificial intelligence applied to contemporary dance.”

At this stage, adolescents are not only exploring who they are, but also who they want to be in the world. It’s the moment they face the dreaded and glorious leap to college, work, or that mysterious limbo where you’re not quite sure what you’re doing with your life—but you sign up for everything anyway. Parents shift from superheroes to emotional consultants: always available, but not too involved… unless things get serious.

From Piaget’s perspective, this stage still falls under formal operations. That means adolescents are capable of thinking abstractly, logically, hypothetically, and critically. They can construct theories about the universe, debate politics, question the global economic system… and still forget to take out the trash. Cognitive development advances, yes—but household responsibility maturity remains highly selective.

Vygotsky, of course, also has a say. For him, social interaction remains the heart of learning. And now more than ever, the peer group becomes a crucial influence. Friends are not just party partners or late-night study buddies—they are mirrors for self-reflection, identity references, and sometimes moral compasses (even if those compasses occasionally spin wildly off course).

And let’s not forget the crash course in “real life”: rush-hour public transportation, overpriced lunches that don’t come with juice and soup, and the existential anxiety of having to choose a career that “defines your future” when you’re still unsure what you want for lunch. This is when you hear unforgettable conversations, like: “Mom, I’m thinking about studying philosophy, opening a café in Iceland, or maybe going into performance art. What do you think?”

This stage also brings the risks and temptations of adult life: addictions, poor decisions, impulsivity, and friendships that sometimes cause more harm than good. That’s why the parental role becomes more subtle, but no less important. It’s about being present without invading, guiding without imposing, and learning when to step in and when to let them figure it out—even if that means watching them make painful mistakes with the hope that every fall becomes a lesson.

But it’s not all chaos. This stage is also deeply beautiful. It’s when you see your child begin to shine in their own right, make brave decisions, discover real passions, and form relationships that nourish them. Conversations evolve: no longer just about homework, but about the meaning of life, social justice, love, spirituality, and dreams. Suddenly, that kid who once cried because their cookie broke can now talk with you about systems of power, climate crises, or how to heal a broken heart.

Speaking of cookies… the cookie crisis also evolves. It’s no longer about uneven halves—it’s about questioning whether the cookie represents something more. Was that really the cookie I wanted? Does the kind of cookie I choose define me? Why do I always pick cookies that break? Should I stop eating cookies and start a more mindful diet? And you, as the adult, can only offer a smile, maybe a hug, and remind them that it’s okay not to have all the answers. That sometimes, even a broken cookie still tastes good. And that in life, just like with cookies, what really matters isn’t the shape—but the flavor it leaves behind.

Because growing up isn’t about not breaking cookies anymore—it’s about learning to enjoy them, even when they’re not perfect. And walking beside them through that journey, even from a distance, remains one of the greatest acts of love.

La adolescencia tardía

La adolescencia tardía, esa etapa gloriosa que comienza más o menos entre los 17 y los 21 años (aunque a veces parece extenderse hasta los 30 dependiendo del caso), es un momento de grandes cambios, decisiones trascendentales, preguntas existenciales y, claro, crisis de identidad al por mayor. Es la fase en la que los hijos empiezan a vivir una especie de independencia con horario, donde ya pueden irse de casa… pero regresan a lavar ropa y pedir mercado. Ya no solo te contradicen por deporte, sino que además estudian carreras con nombres raros que tú ni sabías que existían como “¿Neurociencia computacional con enfoque en inteligencia artificial aplicada a la danza contemporánea?»

En esta etapa, los adolescentes ya no solo están explorando quiénes son, sino quiénes quieren ser en el mundo. Es el momento en que se enfrentan al temido y glorioso salto a la universidad, al trabajo o a ese misterioso limbo donde uno no sabe bien qué hacer con su vida, pero igual se apunta a todo. Aquí, los papás dejan de ser los súper héroes infalibles para convertirse en una especie de consultores emocionales: siempre disponibles, pero sin interferir demasiado… a menos que la cosa se ponga grave.

Desde la mirada de Piaget, esta etapa sigue dentro de las operaciones formales. Es decir, los adolescentes ya pueden pensar de manera abstracta, lógica, hipotética y crítica. Pueden construir teorías sobre el universo, debatir sobre política, cuestionar el sistema económico mundial… y olvidarse de sacar la basura. Porque sí, el desarrollo cognitivo avanza, pero la madurez en las responsabilidades del hogar sigue siendo selectiva.

Ahora bien, Vygotsky no se queda atrás. Para él, la interacción social sigue siendo el núcleo del aprendizaje, y aquí más que nunca, el grupo de pares se convierte en una influencia crucial. Los amigos no solo son compañeros de fiesta y desvelo, sino también espejos en los que los adolescentes se ven reflejados, referencias para definir su identidad y hasta brújulas morales (aunque a veces esas brújulas estén un poco desorientadas).

Y claro, también está el descubrimiento del mundo real: el transporte público en hora pico, el precio de los almuerzos que no vienen con juguito y sopa, y la angustia existencial de tener que escoger una carrera que «definirá su futuro» cuando todavía ni saben qué quieren comer ese dia. Es aquí donde surgen conversaciones inolvidables con frases como: «Mamá, estoy pensando en estudiar Filosofía, abrir un café en Islandia o quizás dedicarme al arte performativo. ¿Qué opinas?»

En esta etapa también aparecen los riesgos y tentaciones del mundo adulto: las adicciones, las malas influencias, las decisiones impulsivas y las amistades que a veces son más peligrosas que útiles. Por eso, el rol de los padres es más sutil pero no menos importante. Recuerden que se trata de estar presentes sin invadir, de ofrecer guía sin imponer, y de tener la sabiduría para distinguir cuándo intervenir y cuándo dejar que los hijos aprendan por sí mismos… incluso si eso significa verlos cometer errores dolorosos con la esperanza de que cada tropiezo se convierta en aprendizaje.

Pero no todo es caos. Esta etapa también es profundamente hermosa. Es cuando ves a tu hijo o hija empezar a brillar con luz propia, tomar decisiones valientes, encontrar pasiones genuinas y construir relaciones que los nutren. Es una fase en la que la conversación cambia: ya no es solo sobre deberes escolares, sino sobre el sentido de la vida, la justicia social, el amor, la espiritualidad, los sueños. De repente, ese niño que lloraba porque se le partió la galleta ahora puede tener una conversación contigo sobre los sistemas de poder, las crisis climáticas o cómo curar un corazón roto.

Y hablando de la galleta… en esta etapa, la crisis de la galleta rota se transforma. Ya no se trata de dos mitades desiguales, sino de cuestionar si la galleta en sí representa algo más: ¿era esa galleta lo que realmente quería? ¿Me define el tipo de galleta que elijo? ¿Por qué siempre elijo galletas que se rompen? ¿Debería dejar de comer galletas y empezar una dieta más consciente? Y tú, como adulto, solo puedes ofrecer una sonrisa, tal vez un abrazo, y recordarles que está bien no tener todas las respuestas. Que a veces, la galleta rota también sabe bien… y que en la vida, igual que con las galletas, lo importante no es la forma, sino el sabor que dejan.

Porque crecer no es dejar de romper galletas, sino aprender a disfrutarlas incluso cuando no son perfectas. Y acompañarlos en ese proceso, aunque sea desde la distancia, sigue siendo una de las formas más grandes de amor.