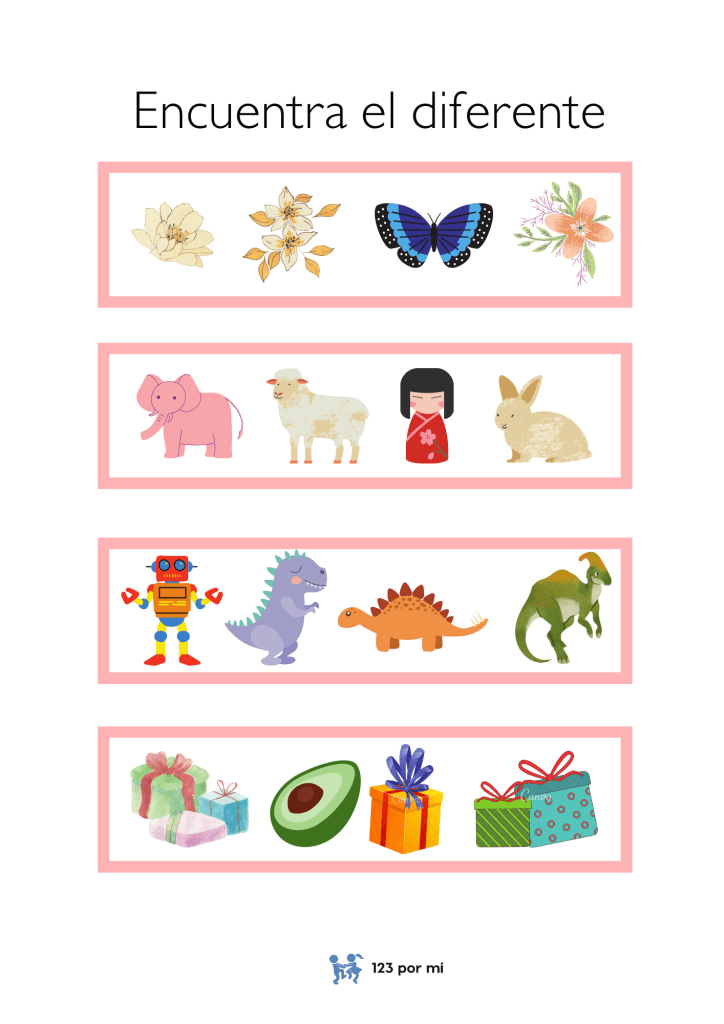

Encuentra el diferente

Inside Out 2: New Emotions, New Fears, New Me

If the first Inside Out taught us that sadness was also important, Inside Out 2 comes to remind us of something harder to accept: growing up hurts. And not because it’s tragic, but because it involves losing versions of oneself, living with new emotions, and experiencing—for the first time—an emotional turmoil that can’t be explained with emojis.

Riley is now 13 years old. And what seems like a small leap in age is, from the perspective of developmental psychology, a hormonal, neurological, and social earthquake. Adolescence begins, and with it, a complete reconfiguration of the emotional brain. More complex emotions appear: Anxiety, Envy, Shame, and Ennui (that teenage boredom with a French accent that we didn’t know had a name). These are emotions that don’t replace Joy, Sadness, or Anger, but rather disorganize the entire system… because growing up is about reordering from chaos.

From Erik Erikson’s perspective, this stage of development is called the search for identity vs. role confusion. Riley is no longer just a happy girl who plays hockey. Now she’s starting to wonder who she is, who she wants to be, who her friends see as her, what people think, how to fit in without ceasing to be herself. It’s the beginning of the adolescent whirlwind, where the construction of the «self» is a puzzle that changes shape every day.

In this context, anxiety appears as the emotional protagonist. And it’s no coincidence. From neuroscience, we know that the amygdala (the fear center) becomes especially active in adolescence. Everything becomes more intense, more personal, more dangerous. What was once a mistake is now a social catastrophe. What was once a passing emotion is now an internal roller coaster. Anxiety, in the film, is not the villain. It’s an emotion that wants to help, that tries to anticipate dangers, but ends up overcontrolling everything. Exactly as it happens in real life.

Inside Out 2 also presents another fascinating change: the deconstruction of the «self.» In the first film, Joy showed us the Personality Islands. In this one, we discover the Sense of Self, which isn’t something solid but a crystal under construction, filled with internal beliefs that are activated by emotions. Riley is no longer defined only by what she does, but by what she believes about herself. «I’m a good friend,» «I’m a good player,» «I’m someone you can count on»… Until anxiety begins to question each one.

This connects directly to the concept of self-schemas: the beliefs we have about who we are. When these self-schemas are threatened (because we lose a game, because we fight with a friend, because we’re rejected), we feel our entire identity shaken. Riley experiences this crisis. And like many teenagers, she tries to fit in. She hides behind what she thinks others want to see. She distances herself from who she was. She «betrays» herself in order to belong.

But the film, with the emotional sweetness that only Pixar achieves, reminds us of something vital: we can’t build a healthy identity if we exclude our uncomfortable emotions. Joy realizes she can’t bury difficult emotions. Literally. She had pushed them to the back of her mind. But without them, Riley’s self becomes fragile, false, anxious.

The solution? Integrate. Let them all speak. Let sadness have a voice. Let shame emerge. Let anxiety not take control, but not be expelled either. Because forming a healthy identity means learning to live with all that we are. Not just the pretty things.

Inside Out 2 isn’t just a sequel. It’s an emotional lesson. It teaches us that growing up isn’t about ceasing to be who we were, but rather integrating new versions of ourselves, embracing new emotions, and understanding that the self isn’t defined by control, but by connection.

And yes: sometimes, to grow, you first have to fall apart a little inside.

Intensamente 2: emociones nuevas, miedos nuevos, yo nuevo

Si la primera Intensamente nos enseñó que la tristeza también era importante, Intensamente 2 llega para recordarnos algo más difícil de aceptar: crecer duele. Y no porque sea trágico, sino porque implica perder versiones de uno mismo, convivir con emociones nuevas, y vivir —por primera vez— un desorden emocional que no se puede explicar con emojis.

Riley tiene ahora 13 años. Y lo que parece un pequeño salto en edad es, desde la psicología del desarrollo, un terremoto hormonal, neurológico y social. Comienza la adolescencia, y con ella, una reconfiguración completa del cerebro emocional. Aparecen emociones más complejas: Ansiedad, Envidia, Vergüenza, y Ennui (ese hastío adolescente con acento francés que no sabíamos que tenía nombre). Son emociones que no vienen a reemplazar a Alegría, Tristeza o Furia, sino a desorganizar el sistema por completo… porque crecer es eso: reordenar desde el caos.

Desde el enfoque de Erik Erikson, esta etapa del desarrollo se llama búsqueda de identidad vs. confusión de roles. Riley ya no es solo una niña feliz que juega hockey. Ahora empieza a preguntarse quién es, quién quiere ser, quién la ven como sus amigas, qué piensa la gente, cómo encajar sin dejar de ser ella. Es el inicio del torbellino adolescente, donde la construcción del “yo” es un rompecabezas que cambia de forma cada día.

En este contexto aparece Ansiedad como la protagonista emocional. Y no es casual. Desde la neurociencia, sabemos que la amígdala (el centro del miedo) se vuelve especialmente activa en la adolescencia. Todo se vuelve más intenso, más personal, más peligroso. Lo que antes era un error ahora es una catástrofe social. Lo que antes era una emoción pasajera ahora es una montaña rusa interna. Ansiedad, en la película, no es la villana. Es una emoción que quiere ayudar, que intenta anticiparse a los peligros, pero termina sobrecontrolando todo. Exactamente como sucede en la vida real.

Intensamente 2 también presenta otro cambio fascinante: la deconstrucción del “yo”. En la primera película, Joy nos mostraba las Islas de la Personalidad. En esta, descubrimos el Sentido del Yo, que no es algo sólido sino un cristal en construcción, lleno de creencias internas que se activan con emociones. Riley ya no se define solo por lo que hace, sino por lo que cree de sí misma. “Soy una buena amiga”, “Soy una buena jugadora”, “Soy alguien con quien se puede contar”… Hasta que la ansiedad empieza a cuestionar cada una.

Esto conecta directamente con el concepto de autoesquemas: las creencias que tenemos sobre quiénes somos. Cuando esos autoesquemas se ven amenazados (porque perdemos un partido, porque nos peleamos con una amiga, porque nos rechazan), sentimos que se tambalea nuestra identidad entera. Riley vive esa crisis. Y como muchos adolescentes, intenta adaptarse. Se esconde detrás de lo que cree que los demás quieren ver. Se aleja de lo que era. Se “traiciona” para pertenecer.

Pero la película, con la dulzura emocional que solo Pixar logra, nos recuerda algo vital: no podemos construir una identidad saludable si excluimos nuestras emociones incómodas. Alegría se da cuenta de que no puede enterrar las emociones difíciles. Literalmente. Las había mandado al fondo. Pero sin ellas, el “yo” de Riley se vuelve frágil, falso, ansioso.

¿La solución? Integrar. Dejar que todas hablen. Que la tristeza tenga voz. Que la vergüenza se asome. Que la ansiedad no tome el control, pero que tampoco sea expulsada. Porque formar una identidad saludable es aprender a convivir con todo lo que somos. No solo con lo bonito.

Intensamente 2 no es solo una secuela. Es una lección emocional. Nos enseña que crecer no es dejar de ser quienes fuimos, sino integrar versiones nuevas, aceptar emociones nuevas, y entender que el yo no se define por el control, sino por la conexión.

Y sí: a veces, para crecer, primero hay que desmoronarse un poquito por dentro.

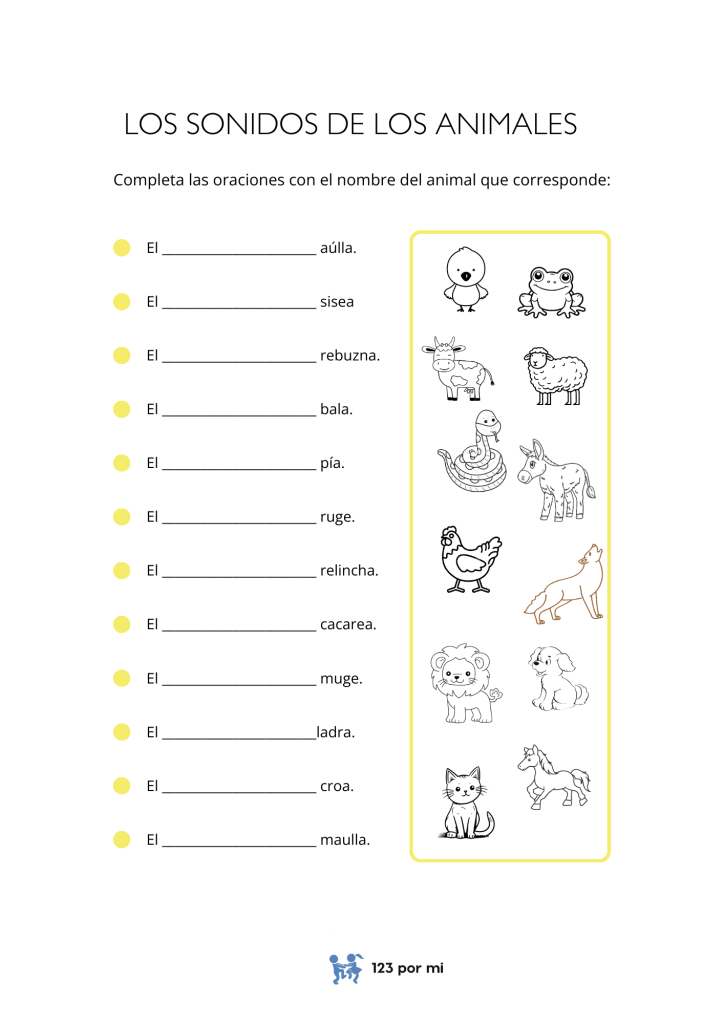

Completa las oraciones

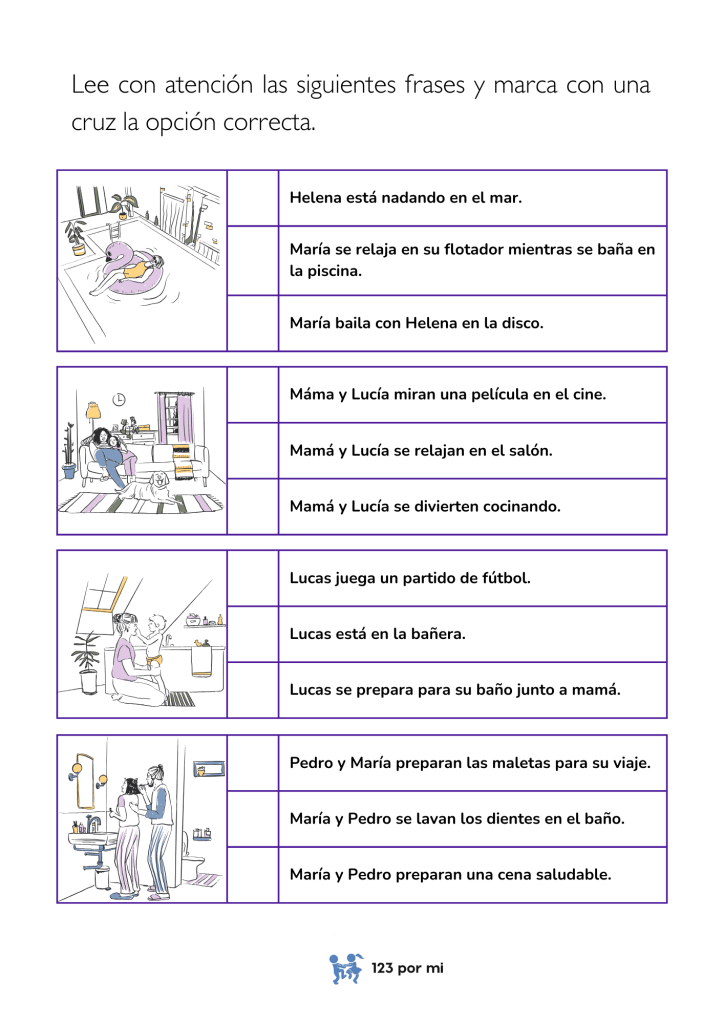

Marca la opción correcta

Marca la opción correcta

Adolescence

And just when you thought you had mastered the art of fixing a broken cookie without triggering the apocalypse… adolescence arrives. That mystical, chaotic, and deeply transformative stage in which your child—who once believed you were an all-knowing being with answers to everything—now suspects you don’t even know what you’re doing with your life. And the worst part? They might be right.

Adolescence isn’t just another stage; it’s almost a full system reboot. It starts around age 11 or 12 and extends to 18 or even beyond (because, as we know, maturity doesn’t come with a legal ID). Unlike earlier stages, this one isn’t just about learning how to walk, share, or not cry over a broken cookie. Now it’s about deeper stuff: Who am I? What do I want to do with my life? Why do my parents breathe so loudly? You know—daily existential questions.

As we saw in the previous episode, from Piaget’s perspective, this is the stage of formal operations—the fourth and final stage of his cognitive development theory. Here, adolescents don’t just think in concrete terms anymore; they develop the ability to think abstractly, logically, and systematically. That means they can form hypotheses, imagine possible futures, question norms… and argue with you for thirty minutes about why they should be allowed to watch videos until 3 a.m. with lines like, “But I manage my sleep well, Mom.”

This abstract thinking is a gift to science, art, and philosophy… but it also gives rise to conversations like: “Nothing matters, everything is an illusion, why study if we’re all going to die anyway?” Bravo—Nietzsche would be proud. But you just wanted them to finish their math homework.

Meanwhile, our dear Vygotsky continues to insist that learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum, but through interaction with others. And now a new character enters the scene: the peer group. In childhood, the adult was the central figure. Now, the adolescent turns toward their social group. Friends are no longer just playmates—they become mirrors and references. What they say, do, or think matters a lot. So much, in fact, that your teen might change the way they dress, speak, or even their music taste just to fit in. Yes, even if that means listening for hours to songs that sound, to you, like they were created for an alien summoning ritual.

Vygotsky would say this isn’t betrayal—it’s a natural part of development. Adolescents need to test themselves in new environments, to contrast what they learned at home with what they see in the world. It’s part of building their identity, a concept that Erik Erikson—another classic in psychology—called the “search for self.” For Erikson, this stage is marked by the conflict between “identity vs. role confusion.” Basically, they’re in full: “Who am I and what am I supposed to do with everything I feel, think, and want?” mode.

And of course, in the midst of this internal revolution, the relationship with parents changes too. They no longer want to be looked at the same way, or be called “my little one” in front of friends, but if they feel insecure, they seek your company like when they were five. Adolescence is a stage where they crave more freedom—but also more containment (though they’ll never admit it). They want to be heard, not lectured. And most of all, they want to feel like their voice matters, even as they’re still learning how to use it wisely.

Academically, this stage brings new challenges. Adolescents no longer learn through imitation or repetition, but because something makes sense to them—because it connects with their world or sparks emotion. (Hello, passionate teachers—you work magic here!). The problem is that the education system often doesn’t match the emotional rhythm of this stage. It’s not uncommon to see brilliant students become disengaged—not due to lack of ability, but due to lack of connection.

That’s why supporting an adolescent is a delicate balancing act. It’s not about imposing, but about accompanying; not about controlling, but about guiding. And yes, sometimes that support happens through awkward silences, eye rolls, and locked doors. But there are also beautiful moments—deep conversations in the middle of the night, unexpected hugs you didn’t see coming.

And if you’re wondering about the cookie, don’t worry—it’s still part of the story. It’s just no longer literal. Now, the broken cookie is the message left on read, the Instagram story where they weren’t tagged, the misunderstanding with their best friend, or the “you left me on seen” that turns into a full-blown Greek tragedy. They no longer cry because the cookie broke, but because the world breaks their heart in small doses, and they don’t yet know how to put the pieces back together.

That’s where you come in—with your unconditional love, infinite patience, and your gift for being present without overwhelming, for holding space without suffocating. Because even if they don’t say it, they still need you to remind them that everything’s going to be okay. Even when their emotional cookie is shattered into crumbs.

Nuevo episodio de Dialoguemos la infancia

La adolescencia

Y entonces, cuando por fin creías que habías dominado el arte de armar una galleta rota sin que se desate el apocalipsis… llega la adolescencia. Esa etapa mística, caótica y profundamente transformadora en la que tu hijo, que antes creía que eras un ser todopoderoso con respuestas para todo, ahora sospecha que ni tú mismo sabes lo que estás haciendo con tu vida. Y lo peor: probablemente tenga razón.

La adolescencia no es una etapa más, es casi un reinicio completo del sistema. Comienza aproximadamente a los 11 o 12 años y se extiende hasta los 18 o más (porque la madurez no llega con la cédula, como bien sabemos). A diferencia de las etapas anteriores, aquí ya no se trata solo de aprender a caminar, a compartir o a no llorar por una galleta partida. Ahora el asunto es mucho más profundo: ¿Quién soy? ¿Qué quiero hacer con mi vida? ¿Por qué mis papás respiran tan fuerte? Ya saben cuestiones existenciales del día a día

Como vimos en el episodio anterior, desde la perspectiva de Piaget, este es el momento de la etapa de operaciones formales, la cuarta y última de su teoría del desarrollo cognitivo. En ella, el adolescente ya no piensa solo en términos concretos, sino que desarrolla la capacidad de pensar de forma abstracta, lógica y sistemática. Es decir, ahora pueden formular hipótesis, imaginar futuros posibles, cuestionar normas… y debatirte durante media hora por qué sí deberían poder ver videos hasta las 3 a.m. cuando salen con un “porque yo manejo bien el sueño, mamá”.

Este pensamiento abstracto es una maravilla para la ciencia, el arte y la filosofía… pero también es el origen de conversaciones del tipo: “Nada tiene sentido, todo es una ilusión, ¿para qué estudiar si al final todos vamos a morir?”. Aplausos, Nietzsche estaría orgulloso, pero tú solo querías que hicieran la tarea de matemáticatica.

Por su parte, nuestro querido Vygotsky no se queda atrás. Él sigue insistiendo en que el aprendizaje no ocurre en el vacío, sino en interacción con los demás. Y aquí entra un nuevo protagonista en escena: el grupo de pares. Durante la infancia, el adulto era la figura central. Ahora, el adolescente empieza a volcarse hacia su grupo social. Los amigos ya no son solo compañeros de juego, son espejos y referentes. Lo que dicen, hacen o piensan, importa mucho. De hecho, importa tanto que pueden cambiar su forma de vestir, hablar o hasta sus gustos musicales con tal de encajar. Sí, incluso si eso significa escuchar por horas canciones que parecen salidas de un ritual alienígena para ti.

Vygotsky diría que este cambio no es una traición, sino parte natural del desarrollo. El adolescente necesita probarse en otros contextos, contrastar lo que aprendió en casa con lo que ve en el mundo. Es parte del proceso de construir su identidad, un concepto que Erik Erikson —otro clásico de la psicología— llamó “búsqueda del yo”. Para Erikson, esta etapa está marcada por el conflicto entre “identidad vs. confusión de roles”. Básicamente, están en modo: “¿Quién soy y qué hago con todo esto que siento, pienso y deseo?”

Y claro, en medio de toda esta revolución interna, la relación con los padres también se transforma. Ya no quieren que los mires como antes, ni que les digas “mi chiquito” frente a sus amigos, pero si se sienten inseguros, buscan tu compañía como cuando tenían cinco años. La adolescencia es esa etapa en la que necesitan más libertad, pero también más contención (aunque jamás lo admitan). Quieren ser escuchados, pero no sermoneados. Y, sobre todo, quieren sentir que su voz importa, aunque aún estén aprendiendo a usarla con sabiduría.

En lo académico, esta etapa trae nuevos desafíos. El adolescente ya no aprende por imitación o repetición, sino porque algo le hace sentido, porque conecta con su mundo o porque le despierta una emoción (¡hola, profes apasionados, ustedes hacen magia aquí!). El problema es que el sistema educativo muchas veces no se adapta al ritmo emocional de esta etapa. No es raro ver estudiantes brillantes desmotivados, no por falta de capacidad, sino por falta de conexión.

Por eso, acompañar a un adolescente es un ejercicio de equilibrio fino. No se trata de imponer, sino de acompañar; no de controlar, sino de guiar. Y sí, a veces ese acompañamiento se da entre silencios incómodos, ojos en blanco y puertas cerradas con llave. Pero también hay momentos hermosos, conversaciones profundas en medio de la madrugada, abrazos repentinos que no te esperabas.

Y si te estás preguntando por la galleta, no te preocupes, ella sigue siendo parte del relato. Solo que ahora, la galleta rota no es literal. Es el mensaje que no fue contestado, la historia de Instagram donde no los etiquetaron, el malentendido con su mejor amigo o el “me dejaste en visto” que se convierte en tragedia griega. Ya no lloran porque la galleta se partió, sino porque el mundo les parte el corazón en pequeñas dosis, y todavía no saben cómo armarlo de nuevo. Ahí es donde entras tú, con tu amor incondicional, tu paciencia infinita y tu habilidad de estar sin invadir, de contener sin asfixiar. Porque aunque no lo digan, aún necesitan que les recuerdes que todo va a estar bien. Incluso cuando la galleta emocional esté hecha trizas.