Categoría: English

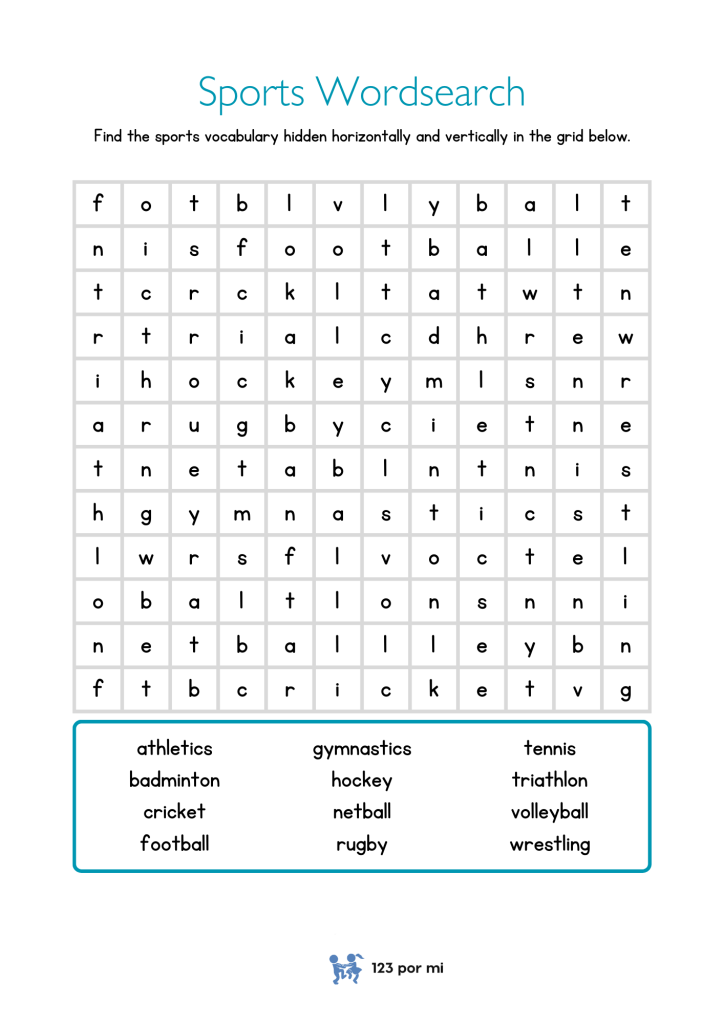

Sports wordsearch

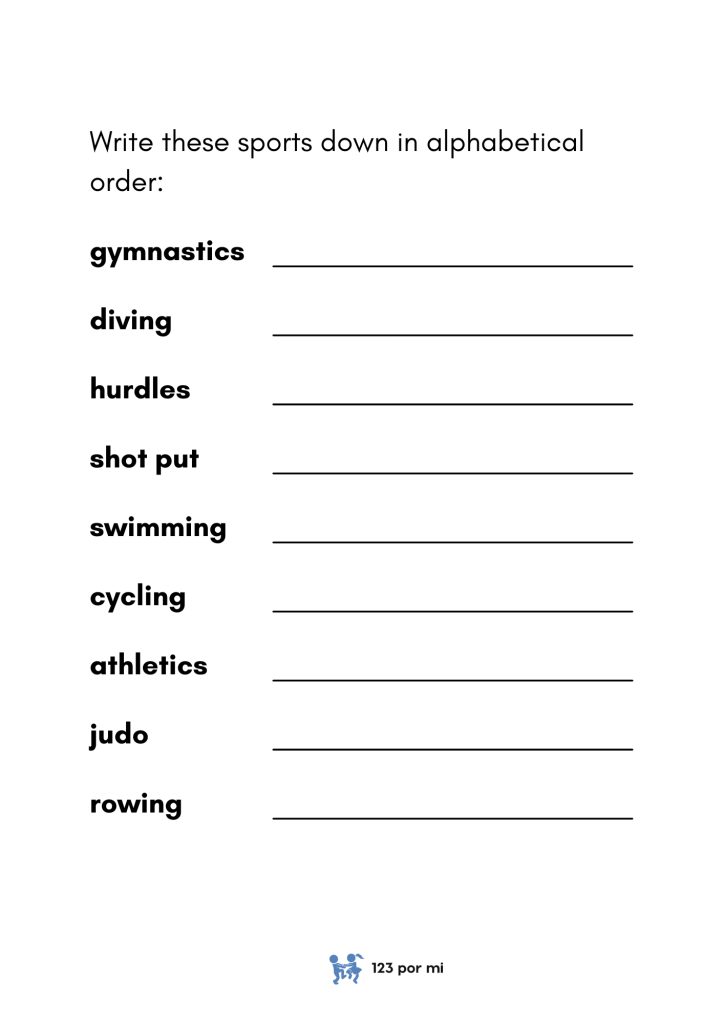

Write in alphabetical order

The formal operational stage

The formal operational stage, according to Jean Piaget, begins around the age of 12 and extends into adulthood. This is when a child’s brain (now on the verge of adolescence) undergoes a kind of «software update» and suddenly starts thinking in a logical, abstract, and systematic way. It’s no longer just about understanding that two differently shaped glasses can hold the same amount of juice — it’s about pondering existential dilemmas, questioning social justice, challenging established rules… and, of course, debating you like a constitutional law expert (even if they still can’t find their socks).

In this stage, adolescents develop what Piaget called hypothetico-deductive reasoning. This means they no longer need to see something to understand it: they can imagine situations, form hypotheses, and predict outcomes. It’s when they start saying things like, “If all humans were invisible, how would we know we exist?” while you’re just trying to get them to eat dinner. It’s also the era of ambitious projects: today they want to be musicians, tomorrow astronauts, and the next day environmental activists — all while rehearsing a TikTok dance routine.

Egocentrism doesn’t entirely disappear, but it changes shape. They no longer believe the world literally revolves around them; instead, they feel like everyone is watching and judging their every move. This is known as the imaginary audience: the belief that they’re constantly under observation. That’s why they choose their outfits with the precision of a designer at Fashion Week and can spend hours deciding if their post has the right number of emojis. Enter the personal fable: the idea that their experiences are completely unique, incomparable, and that no one (especially you) could possibly understand them — even if you just asked them to turn down the music.

From Vygotsky’s perspective, the social environment remains key. Even though adolescents are now more capable of learning on their own, they still need dialogue, guidance, and interaction with adults and peers to shape their thinking. The famous Zone of Proximal Development now becomes filled with debates, reasoned arguments, and intellectual challenges. Relationships with parents, teachers, friends, and even public figures begin to shape their worldview. That’s why a seemingly casual conversation about politics or movies can turn into a passionate defense of human rights, indie cinema, or the moral superiority of cats over dogs.

Academically, this stage is when many essential skills become solid: understanding complex texts, solving multi-variable math problems, and analyzing information from different perspectives. They can now grasp metaphors, irony, and double meanings (which makes conversations either much more fun… or much more confusing if you use sarcasm too lightly).

It’s also the time when identity begins to take clearer form. They no longer just imitate those around them — they choose who they want to be like. They research, explore, and try out different versions of themselves. Today they’re vegetarian, tomorrow Buddhist, and the next day back to being a die-hard fan of a K-pop band. And in the midst of all these changes, parents remain a fundamental compass, even if it doesn’t always seem that way. Supporting them without imposing, listening without judging, and being present without invading becomes a high-level skill (and yes, it may require a lot of chocolate and deep breathing).

Speaking of high-level skills, we reach a critical point in this journey: the cookie. Because even though they can now solve quadratic equations and discuss climate change, if someone breaks a cookie in half without consulting them, it might spark a diplomatic conflict of international proportions. Not because they don’t understand it’s still the same cookie, but because now they want to decide how it’s broken, who it’s shared with, and whether that cookie represents a symbolic act of respect. At this stage, every cookie counts… especially if there’s a camera nearby and they want to make a speech about the fair distribution of household resources.

So yes, adolescence can feel like an emotional rollercoaster, but it’s also a wonderful stage where the doors to complex thought, reflection, and ideal-building begin to open. All it takes is patience, a sense of humor… and plenty of evenly divided cookies.